A struggle for identity?

A century on from what Armenians call the ‘first genocide of the 20th century’ Joe Nerssessian investigates the fight for recognition and what it means to be an Armenian living in the UK.

Israel Vahan Pilikian was a young teenager in 1915 when he found himself marching through the Syrian desert with hundreds of thousands of others. Expelled from the house he built with his father by Ottoman troops. Over a thousands miles from his home of Khasgal, then a village in the Ottoman Empire, now part of Turkey. He trekked through the treacherous Der El-Zor. Kurdish brutes pillaged the vulnerable and weak. Women threw themselves from a mountain to avoid rape and slaughter. The bodies of those who succumbed to starvation and exhaustion lay in the scorching sun. In the eyes of Armenians, this was genocide.

100 years on and modern day Turkey dispute the events of 1915 were a genocide orchestrated by their predecessors in the Ottoman Government. Hundreds of thousands of Armenians were forced to flee to the Middle East or Western Countries. The Armenian government estimate up to ten million Armenians are now living outside of the modern day Republic, a small stretch of former Soviet land wedged between Turkey, Azerbaijan, Iran and Georgia. On April 24th this year, Armenians across the globe will commemorate those who died, 1.5 million at their estimation, and simultaneously demand their governments recognise the event as genocide in order to pressure Turkey.

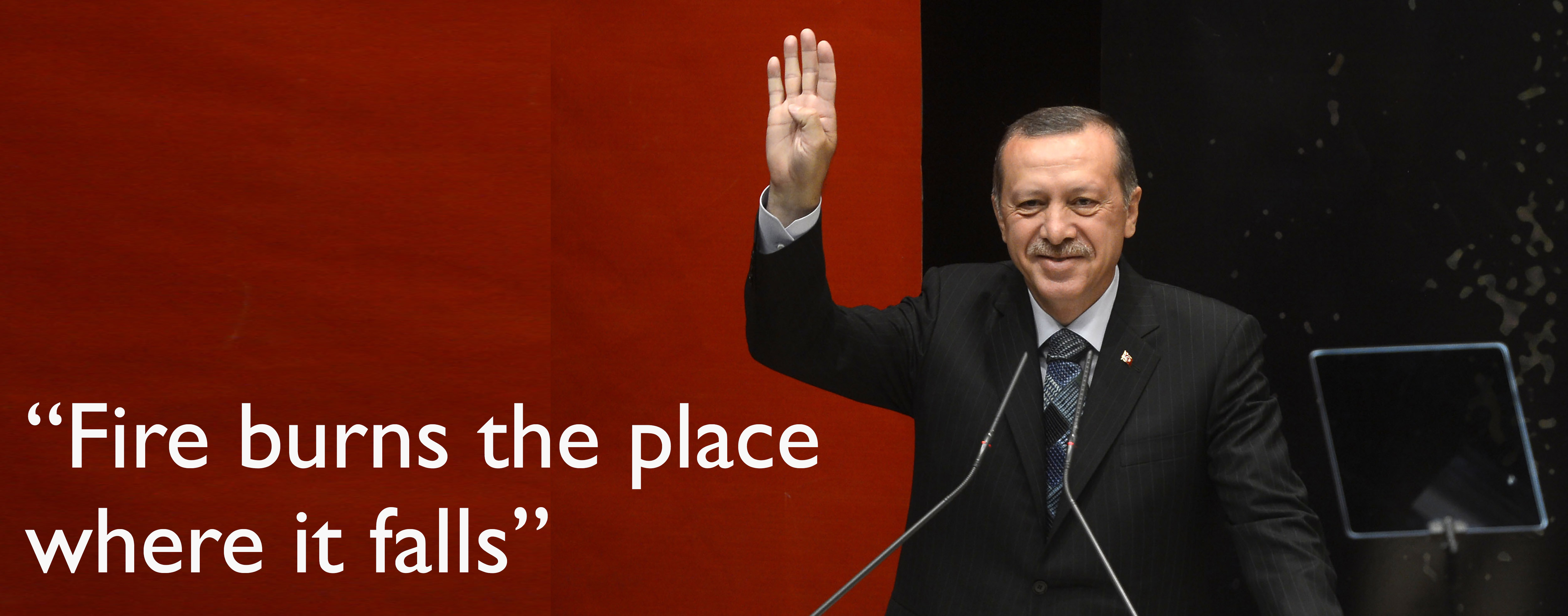

The Turkish Prime Minister refutes these appeals and warns against using the “events of 1915 as an excuse for hostility against Turkey”.

In a statement Prime Minister Erdogan said: “The incidents of the First World War are our shared pain and quotes a Turkish proverb that goes “fire burns the place where it falls”.

The British government also refuses to condemn the massacres as genocide. This is despite Britain reacting forcefully in the years after 1915. The government of the day said the events were a “crime against humanity” after they issued historian Arthur Toynbee to produce a report on the events.

A book written last year by key legal expert, Geoffrey Robertson QC, highlights how as modern day Turkey has grown in geographical and political importance, recognition by the British Government became less crucial.

Robertson’s book, ‘An Inconvenient Genocide’, argues from a legal perspective how the massacres were genocide and investigates the Foreign Office’s (FCO) attempts to avoid the issue of recognition during the last Labour Government. Their official position then was that the evidence of genocide was not ‘successfully unequivocal” however a private note from 1999 revealed via a Freedom of Information request shows the real reasons behind this decision.

“Given the importance of our relations with Turkey, and that recognising the genocide would provide no practical benefit to the UK or the few survivors of the killings still alive today, nor would it help a rapprochement between Armenia and Turkey.”

This didn’t surprise the 20,000 or so UK Armenians, most of who campaign ferociously for recognition of genocide. But, after a century of disappointment over recognition, retribution and repatriation, how do they maintain an Armenian identity?

Fighting for recognition is part of being Armenian, according to Garen Arevian, who sits on the UK’s Armenian Genocide Centenary Commemoration Committee (AGCCC). He thinks his compatriots should “fight for recognition of genocide because it is simply our duty.”

The AGCCC are planning events throughout 2015 to educate the British public and “promote recognition by our Government”.

Arevian highlights the activity of the Armenian community, when he recalls representatives from over fifty different organisations attending the initial AGCCC meeting.

Photo: Joe Nerssessian

However this obsession with genocide recognition is damaging culture and identity in the London community, argues Dr Krikor Moskofian, who was born in Beirut and now lectures at the London School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS).

“All the human and financial energy is channelled into genocide recognition. If you channel all your efforts in one direction you fail to address the other aspects of communal Armenian life. That is why we have cultural stagnation in this community.

“I am not saying it (recognition) is not important but I am concerned there are more important issues such as promoting Armenian language and literature in the community.”

Dr Moskofian teaches Western Armenian, a UNESCO endangered language as it differs from the language spoken in the modern day Armenia Republic.

He may have a point, only 40% of the UK community can speak either language, and just 10% can read or write it, according to Misak Ohanian, who runs a charity supporting Armenians in the UK.

Ohanian was born in Cyprus but his family were forced to escape in the 1960’s after inter-communal fighting with Turks. His grandfather had survived the genocide and was uprooted for the second time. In 1986 Misak set up the Centre for Armenian Information and Advice “to help Armenians living in the UK understand their rights”.

Despite living in the UK for 45 years and his day-to-day close relationship with Armenians, Ohanian admits he still ‘feels like a fish out of water’.

“I am not Armenian. I am Armenian diaspora. We are all different styles of Armenian. It doesn’t mean I’m not proud. In the same way you have Greek style yoghurt, Parma ham style ham. It’s not the real thing. It is a style. It has been processed down into different versions. It has a right to exist in owns right but it’s not the purity of what it was.”

However, Ohanian remains an active member in the community and his organisation raised over £10,000 for Armenia after a tragic earthquake in the 1980’s. So although his roots may feel unsettled or ‘disjointed’ he, like a large number of the diaspora, still attempts to connect with the modern day Republic.

This is a familiar aspect of Armenian identity, according to MP Stephen Pound, who thinks their London community is “remarkable”.

Many of the UK community live in Pound’s constituency of Ealing North, and a substantial number are based in the wider West London area.

He has supported Armenians in fighting for recognition, arguing their case in the House of Commons and speaks so highly of the community that they could perhaps act as a blue print for other minorities settling in Britain.

“They integrated but didn’t assimilate. They have kept this Armenian identity and have been here for such a long time and so incredibly successful and virtually crime free. It’s the most extraordinary community.”

As well as language – music, art, sport and religion are also important aspects of maintaining an identity. The Armenian Republic hosts a Pan-Armenian games every four years, inviting diaspora’s from cities all over the world to compete against each other in a series of sporting events. They also launched an appeal last year to encourage members of the diaspora to contribute to the Armenian language Wikipedia pages.

West London is also home to two Armenian churches, St Sarkis in High Street Kensington and St Yeghiche in South Kensington.

St Sarkis is built in keeping with traditional Armenian churches, built in 1922 and financed by Calouste Gulbenkian, the driving force behind the Turkish Petroleum Company.

Father Shnork of St Sarkis, believes the presence of his church supports identity by using “Armenian language, Armenian songs, music and even architecture.”

Father Shnork grew up in Armenia and moved to London 20 years ago. He says maintaining identity in a diaspora is a ‘conscious effort’.

However for UK born student Vahe Boghosian, who runs the Armenian society at University College London (UCL) identifying yourself as Armenian is simple.

“Culture is something you can’t explain through numbers or blood. It is something in your heart. It doesn’t matter what you tick on the census or what the numbers say. It is how you feel inside.”

A century on and the Pilikian name does live on. Israel Pilikian survived the terrifying reality of the death marches and wrote memoirs discussing his escape of the massacres. He lived until 1997, dying in London aged 95. His memoirs are kept by his son, Professor Khatchatur Pilikian, who has studied and practiced Armenian culture throughout his life as a musician, painter and writer. Khatchatur believes Armenians living in diaspora need to discover and learn about their own culture in order to maintain identity.

Image: Joe Nerssessian

“Sometimes Armenians are satisfied with having the identity sample by saying ‘I am Armenian’. To understand your identity you have to know it.”

Khatchatur speaks proudly of his parents who both overcame the horrific experiences of 1915, yet still learnt to forgive.

“They never hated the Turkish people because they had help from them. They said it was not a result of what the Turkish people wanted and I am very proud of that heritage.”

Khatchatur strikes a cord and I realise none of the Armenians I have spoken to have shown any hatred for modern Turkey. Further to that, through all my meetings with Armenians and visits to a handful of their 50 or so UK organisations, it’s evident this is a minority that has established itself in a quiet yet persistent manner. The students seem bright, eager and multi-lingual. Religion is important to identity but not an extreme dedication. Culture is valued highly. The community has a definitive Armenian identity yet maintain a British manner. Integrated but not assimilated, as Pound observed. A hundred years on and the Armenians have more than survived.